Hot on the heels of a widely slammed article about global warming, William Broad of the New York Times wisely took on a cooler subject yesterday: big snowflakes. Hey, wasn’t I just talking about that? Someone’s been reading my mail blog.

Broad writes about credible reports of snowflakes the size of frisbees and how this hypertrophy occurs. The really big ones are actually agglomerations of many individual snowflakes (which are, technically speaking, snow crystals). In the process he mentions a certain Ken Libbrecht, who is the reincarnation of Wilson Bentley, the pioneer snowflake photographer, except that Libbrecht is also a physicist who studies the mechanics of snow crystal growth and grows synthetic snowflakes in his lab. As it happens, after posting the previous item and before reading Broad’s article, I had dug out my copy of Libbrecht’s book The Snowflake: Winter’s Secret Beauty and had been struck by a sidebar on page 60:

Doing Your Part

There is a bit of you in every snowflake. That’s because even you, right this moment, are making a contribution to the atmospheric water supply. Water is evaporating from our skin, plus you are putting water right into the air every time you exhale. In fact, you personally put so much water into the air that some of your water molecules almost certainly made it into the snowflakes pictured in this book.

You exhale roughly a liter of water per day into the atmosphere, and most of this water rains or snows back down again within about a week’s time. The total global precipitation is about 1,000,000,000,000,000 (one quadrillion) times greater than the amount of water you exhale, so your impact on the weather is pretty minor.

But even if you contribute only one quadrillionth of the total water content in a snowflake, that is still about 1,000 molecules. It depends on how well things are mixed up in the atmosphere, but there are probably, very roughly, about a thousand of your molecules captured in every snowflake picture. Thank you for your contribution—and keep up the good work.

Initially I was charmed by this idea. But the more I thought about it, the more it bothered me. What does he mean, “a bit of you”? Just because some water molecules happened to pass through me, they’re “me”? Or “mine”? I understand what he’s saying: water that was in me has gone off and got embedded in snowflakes (maybe even, theoretically, after having lived so long, in every snowflake). But obviously I was just a temporary vessel for this water, just as the snowflake is a temporary structure made partly from this same water. As a striking image of the water cycle in action, I rather like Libbrecht’s formulation. I guess I object to considering the water a “bit of me,” rather than the reverse: I was temporarily (momentarily, for the blink of an eye or less) a collection of that molecule of water and that one and that one … (plus molecules of a lot of other stuff, all quite transiently). I mean, it’s not as if I come to own, or even possess in any real sense, the water, or the potassium, or the iron, or anything in me. Even these thoughts are just passing through.

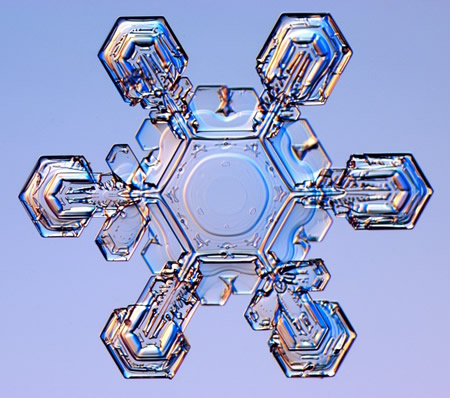

I highly recommend the book mentioned above (I have not seen Libbrecht’s more recent Field Guide to Snowflakes). In passing he mentions Ice IX and Kurt Vonnegut’s fabulous “ice-nine,” which sent me scampering off into the internet, where I found a free copy of Cat’s Cradle to reread. Unlike Vonnegut’s catastrophic fictional substance, the real stuff is “a metastable form of solid water that exists at temperatures below 140 K and pressures between 200 and 400 MPa. It has a tetragonal crystal lattice and a density of 1.16 g/cm3, slightly higher than ordinary ice” (Ice Ih, which is hexagonal, as you can see).

From Ken Libbrecht’s website SnowCrystals.com

Okay, they say tomorrow it’s going to be in the mid-60s (Fahrenheit—which is what, high teens Celsius?). No more snow talk. Happy Vernal Equinox, everyone!