“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9 )

In an autobiographical fragment, Mark Twain recounted his time on the lecture circuit in the early 1870s. His stage appearances alternated with those of Horace Greeley, Josh Billings, Louis Agassiz, and others less notable. Some could be counted on to fill the house; others were “house emptiers.”

In an autobiographical fragment, Mark Twain recounted his time on the lecture circuit in the early 1870s. His stage appearances alternated with those of Horace Greeley, Josh Billings, Louis Agassiz, and others less notable. Some could be counted on to fill the house; others were “house emptiers.”

“There were two women,” Twain writes, “who should have been house emptiers—Olive Logan and Kate Field—but during a season or two they were not. They charged $100, and were recognized house-fillers for certainly two years.”

Twain felt he knew why Kate Field had her moment of fame, but Olive Logan … She strikes a peculiar chord here in the 21st century. “Olive Logan’s notoriety grew out of—only the initiated knew what,” says Twain.

Apparently it was a manufactured notoriety, not an earned one. She did write and publish little things in newspapers and obscure periodicals, but there was no talent in them, and nothing resembling it. In a century they would not have made her known. Her name was really built up out of newspaper paragraphs set afloat by her husband, who was a small-salaried minor journalist. During a year or two this kind of paragraphing was persistent; one could seldom pick up a newspaper without encountering it.

“It is said that Olive Logan has taken a cottage at Nahant, and will spend the summer there.”

“Olive Logan has set her face decidedly against the adoption of the short skirt for afternoon wear.”

“The report that Olive Logan will spend the coming winter in Paris is premature. She has not yet made up her mind.”

Twain provides two more examples that we will skip. The upshot is that Olive Logan’s name was almost universally known, but it was not known for what. Every now and then a person from the boonies would pose the simple question:

“Who is Olive Logan?”

The listeners were astonished to find that they couldn’t answer the question. It had never occurred to them to inquire into the matter.

“What has she done?”

The listeners were dumb again. They didn’t know. They hadn’t inquired.

“Well, then, how does she come to be celebrated?”

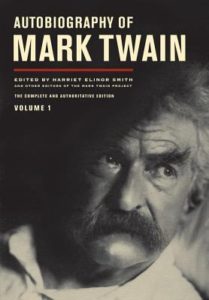

“Oh, it’s about something. I don’t know what. I never inquired, but I supposed everybody knew.” (The Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1, University of California Press, 2010, pp. 151–2)

And so please do not ask me how any of the Kardashians came to be famous, or why they continue to be. Just know they did not invent the trick of being famous for being famous.

* * * * *

Now let us turn to Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby (né David Ross Locke).

Nasby was Twain’s companion at times on the lecture circuit, and Twain’s admiring account of his stage presence is well worth reading. The editors of the three-volume Twain autobiography do us the favor of telling us who this guy was:

David Ross Locke (1833–88) left school at an early age and was apprenticed to a printer, after which he worked on a succession of newspapers. At the outbreak of the Civil War he was the owner and editor of the Bucyrus (Ohio) Journal. It was not until a year later that he published his first satirical piece as Petroleum V. Nasby, an ignorant, bigoted, and boorish character who promoted liberal causes by seeming to oppose them.

Yes, the nineteenth-century Colbert Report.

Nasby (like Colbert) was a true celebrity. According to an obituary, cited by the editors:

These political satires […] were copied into newspapers everywhere, quoted in speeches, read around camp-fires of Union armies and exercised enormous influence in molding public opinion North in favor of vigorous prosecution of the war. Secretary [of the Treasury] Boutwell declared in a speech at Cooper Union, New York, at the close of the war that the success of the Union army was due to three causes—the army, the navy, and the Nasby letters. … These letters were a source of the greatest delight to President Lincoln, who always kept them in his table drawer for perusal at odd times. (Vol. 1, p. 506)

* * * * *

So, is there no new thing under the sun? Rather than try to prove the negative, we can surely agree that much of what passes for novelty is in fact a rediscovery. Forgetting and remembering, back and forth, over and over, such is human life.